One of the most important battles in the Second World War was the Battle of the Bulge. Facts about this deadly battle are given here.

Did You Know?

The Battle of the Bulge was called Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein in German, meaning ‘Operation Watch on the Rhine’. The French called it Bataille des Ardennes, meaning ‘Battle of the Ardennes’, while the Brits and the Americans called it the ‘Ardennes Counteroffensive’.

The Second World War was the deadliest war in human history, and remains a dark stain upon the history of humanity. It contained countless battles that have become the stuff of legend; their victors celebrated, their casualties mourned, their development analyzed and lessons learned.

The Battle of the Bulge is one among such battles. Fought from December 16, 1944, to January 25, 1945, this battle is notable not only for its death count, which stands at the highest among all the battles fought by the Americans in the Second World War, but for the strategies and tactics that led to its eventual outcome.

It was one of the last successful Nazi offensives in the war and caused close to a hundred thousand casualties in the Allied forces, including almost 20,000 deaths.

Here’s some more info about this infamous battle, including the conditions that led to it, its timeline, and its tactical aspects.

Background

To understand the significance of the Battle of the Bulge, it is necessary to know the conditions in Continental Europe before the battle. Here’s a refresher for those who don’t know the timeline of WWII well. History nerds can safely skip this section and advance to the next one.

The year 1944 was notable for the D-Day landings at Normandy. Occurring on June 6, 1944, the Normandy landings were a huge boost for the Allies. It was the first real foothold gained by the Allies against Nazi Germany on Continental Europe; most of the action before it had been confined to the air or the seas. Five beachheads were established in northern France under Allied control.

Following on from the success of D-Day, the Allies, led by the American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, pushed further inland into Continental Europe. The Allied armies pushed into Belgium in early September, and captured several important cities, such as Brussels on September 3 and Antwerp on September 5. This was a serious undermining of Nazi influence in Continental Europe, further exacerbated by the return to Belgium―on September 8―of its government-in-exile, which had been in hiding in England till then. By early November Belgium had been liberated in its entirety.

Meanwhile, Vichy France, a puppet state established by Nazi Germany in the southern regions of France they had not occupied, was slipping from the grasp of Hitler. Paris had been freed on August 25, and the Allied armies had captured crucial cities in Vichy France, such as Lyon, by October.

1944 was also the year when Allied infantry first entered Germany, taking the city of Aachen near the border between Germany and the Netherlands on September 10, the same day that Luxembourg was liberated.

Meanwhile, the Red Army of the Soviet Union had inexorably marched on in the Eastern theater of the War, and had captured several countries held by Nazi Germany. Hitler had given up hope of stopping the Russian advance while still holding fort against the Anglo-American armies.

Leading up to the Battle

These setbacks led Hitler to conceive a counterattack so implausible and difficult to execute that even his most loyal commanders, including Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, had grave doubts about it.

Hitler planned to drive a wedge through the Allied defenses around the Ardennes mountain range in Belgium. Since this area was mountainous and covered in thick forest, the Allies had been lax in their defense of it, with a front of more than 80 miles covered by only 6 divisions. Hitler planned to exploit this weak spot, the same way he had when crossing into France to take Paris. The Germans planned to take the region with a heavy armored charge. The only factor that could hamper the Nazi charge was an attack from the air. The Allied Air Force was far better than that of Nazi Germany, a fact Nazi Generals had pointed out to Hitler, but the Ardennes region would often be covered in fog and heavy clouds, limiting its involvement. Hitler was banking on the weather being favorable to his armies.

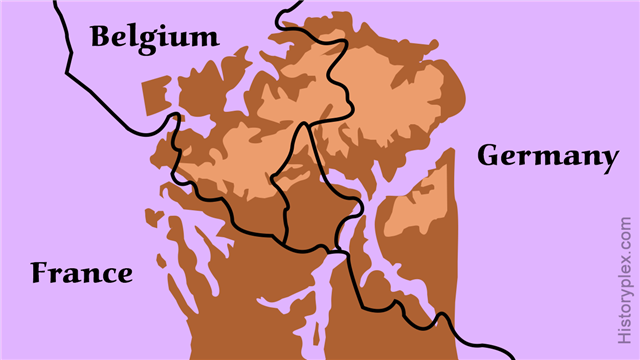

Here’s a map showing the region Hitler planned to take, with the Ardennes mountain range marked. The region between France, Belgium, and Germany is Luxembourg.

Map of Central Europe with the Ardennes region highlighted in progressively darker shades according to elevation

The plans were formulated in utmost secrecy and under the Fuehrer’s personal supervision. Any attempt by Nazi Generals to moderate the offensive was quashed by Hitler.

The eventual objective of the mission was to take Antwerp, northwest of the Ardennes. This was to be achieved by dividing the American and British forces and then surrounding them individually. The northern divisions of the Army would then move on to take Brussels and Antwerp. Antwerp was a crucial city, since it was a major port and was a hub for Allied reinforcements. Though this was considered completely impossible by Nazi Generals, Hitler planned to accomplish all this within one year! The idea behind the plan was that as Hitler considered the Western armies to be inferior in comparison to the Russians, he planned to force them back and enforce a peace treaty favorable to the Germans, giving him time to build more advanced machinery with which he would then take on the Russians.

In the end, Hitler decided that three armies would charge into this battle, with one standing by as backup. The division of labor was as follows:

► The Sixth Panzer Army would lead the charge on Antwerp, attacking the Allied front in the northern region. This army was led by Sepp Dietrich.

► The Fifth Panzer Army would attack the Allied army in the center. Led by Hasso von Manteuffel, the Fifth Panzer Army had the objective of capturing Brussels.

► The Seventh Army, consisting of three infantry divisions, would protect the other two from Allied attacks from the south. This was the only infantry army in the operation, and was led by Erich Brandenberger.

► The Fifteenth Army was stationed between Cologne and Aachen as a backup.

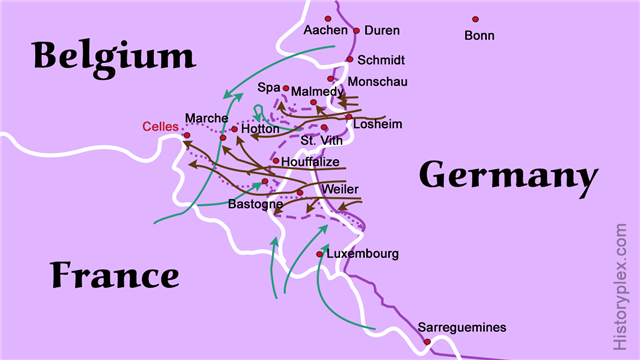

Hitler’s plan for the Ardennes Counteroffensive

The solid lines in the image given above represent the progress actually made by the German Sixth Panzer, Fifth Panzer, and Seventh Armies, and the dashed lines represent what Hitler intended the Armies to achieve. Celles marks the point of the farthest intrusion. The green line represents the ‘bulge’ in the Allied front that gave the battle its commonly used name.

The region between the first and second solid lines was contested by the Sixth Panzer Army, and the region between the second and third solid lines was contested by the Fifth Panzer Army. The Seventh Army stayed further south of the Fifth Army, while the Fifteenth Army stayed further north of the Sixth Panzer Army, between Cologne and Aachen.

Such an attack, consisting of a large number of armored divisions, would require massive amounts of fuel to simply keep the vehicles moving. Though Germany didn’t have enough fuel when the plan was drafted, Hitler intended to appropriate fuel from the Allied establishments they planned to capture.

Timeline and Summary of the Offensive

The German armies made haste to get to their positions on the Eifel Hills in the Eastern slopes of the Ardennes as stealthily as they could. Even radio traffic was minimized to an essential level and most of the movement of the troops was carried out in the night. These drastic measures were largely successful; though the Allies had got word of a potential counteroffensive, they didn’t realize it would occur in the Ardennes. In fact, several troops posted within the Ardennes forests reported suspicious German activity, but the Allied High Command failed to make a connection between all the disparate rumors and tip-offs. The weather also favored the advance of the Nazi armies, as Hitler had counted on, with overcast skies preventing recon aircraft from spotting Nazi bases in the forest.

Northern Front

The battle began at 5.30 am on December 16 with an artillery barrage by the Sixth Panzer Army lasting for about 90 minutes. They were held up by stiff resistance from an American recon platoon as well as heavy snowstorms. Though the snowstorms prevented the entry of Allied aircraft, the German tanks frequently got stuck in the snow, resulting in fuel shortages and general disorganization.

The Fifth Panzer Army headed towards the strategically important cities of St. Vith and Bastogne. Meanwhile, the Seventh Army headed towards Luxembourg to block off potential counterattacks.

At first, the surprise element of the attack really hit home, as the Allies were caught completely off guard in a region they considered a ‘quiet sector’. In addition to this, a few English-speaking German soldiers had infiltrated the Allied camp beforehand and had spread confusion among the forces. They had also sabotaged their communication centers. The US 2nd and 99th Infantry Divisions were the only ones to offer a steady resistance; most of the Allied defenses were reduced to scattered bands of soldiers roaming in the forests and fighting the Germans whenever they happened to encounter them by chance.

Kampfgruppe Peiper, one of the battle formations from the 1st SS Panzer Division of the 6th Panzer Army, was tasked with leading the charge of the 6th Army, and was led by Joachim Peiper. This unit was responsible for a heinous massacre during this battle. Having captured about 125 men from the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, US 7th Armored Division near the town of Malmedy on December 17, the 1st SS Division proceeded to fire upon the unarmed prisoners. About 84-86 prisoners were killed on the spot, and the reasons for firing upon them have not been ascertained even today. This event was known as the Malmedy massacre.

In retaliation, the US Army killed 60 German POWs in an event known as the Chenogne massacre, on New Year’s Day 1945.

Kampfgruppe Peiper intended to advance to the town of Stavelot, but the retreating Americans made it difficult for the Wehrmacht by blowing up bridges in the way, and ransacking fuel depots so that the heavy German machinery was starved of fuel. While the march from Eifel Hills to Stavelot had taken just nine hours when the Germans had crossed into France in 1940, it took them more than a day and a half in 1944 due to the stiff and ruthless American resistance. Peiper eventually captured the towns of Stavelot and Stoumont. However, the Americans retook Stavelot from the Germans and the arrival of the US 82nd Airborne Division cut off Peiper’s escape route. Peiper eventually decided, on December 23, that he had to abandon most of his vehicles due to a severe fuel shortage, and escape to Germany.

Central Region

While the charge of the Sixth Panzer Army fizzled out after a promising beginning, the Fifth Panzer Army achieved the farthest penetration of the Allied front. Unlike the better-equipped Sixth Army, which had to toil for several hours to vanquish American Divisions, the Fifth Army made relatively short work of the scattered 28th and 106th Infantry Divisions. More than 7,000 American soldiers died in the central Schnee Eifel region.

The crossroads town of St. Vith was captured by von Manteuffel on December 23, just as Dietrich’s campaign in the north was on the verge of folding up. Despite the victory, the Germans had fallen grievously behind their own schedule, which demanded that they capture St. Vith by the evening of December 17.

General Montgomery had ordered whatever forces he could muster to guard the bridges on the river Meuse on December 19. These forces, including the British XXX Corps, were successful in halting the onslaught of the Fifth Panzer Army. The farthest penetration from the Germans was achieved by the Fifth Panzer Army by taking the town of Celles in Belgium on December 24.

Southern Front

A major involvement of von Manteuffel’s Fifth Army was the Siege of Bastogne.

The town of Bastogne, important due to its strategic location, was supposed to have been captured in the first or second day of the attack. However, due to the unexpected resistance from American Divisions in the way, the German Seventh Army took until December 21 to encircle Bastogne. After the weather cleared, the Americans defending Bastogne started to receive regular supplies, which helped prolong the defense. The German commander, Lieutenant General Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz sent a message to the Americans, requesting them to understand their seemingly untenable position and surrender the city. To this message, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe sent a famous reply: “NUTS!”.

On Christmas Eve, the Germans were starting to taste success, with their tank charge initially breaking through the American defenses, but eventually all the tanks in the charge were destroyed. On Boxing Day, the siege was broken by the arrival of General Patton’s 4th Armored Division.

January 1945

Realizing that their Armies were failing miserably on all three fronts, Germany launched two new operations on January 1, 1945: Operation Baseplate with the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) and Operation Northwind with the 1st and 19th Armies of the Wehrmacht.

Operation Baseplate (Unternehmen Bodenplatte) was a major offensive aimed at destroying Allied airbases in France and Belgium. This very ambitious operation was a ridiculous failure; the Luftwaffe lost 277 planes thanks to a combination of Allied resistance and friendly fire from German airbases that had not been alerted to the scale of this operation. Though the operation was successful in either destroying or damaging 465 Allied aircraft, the Luftwaffe suffered terribly from the losses, and thereafter remained only a minor force till the end of the War. The Allies, on the other hand, were able to compensate for their damages quickly; since they had access to much better resources than the now-cornered Germans, and the Luftwaffe hadn’t caused major damage to the bases themselves, new airplanes took the place of the damaged ones with little delay.

Operation Northwind (Unternehmen Nordwind), on the other hand, was comparatively a great success. The German Armies attacked the American Seventh Army, which was one of the Armies that had provided reinforcements for the defense of northern posts. This had left the Army quite thin and scattered, and the concentrated German attack completely overwhelmed them. The Seventh Army eventually retreated to the Modder River, where it kept the German onslaught at bay. Despite Hitler’s assurances on January 7 that all offensive forces would be withdrawn from the Ardennes, it was not until January 25 that Operation Northwind was called off.

In January, the shortage of fuel in the German camps really began to show, as they were forced to leave most of their armored vehicles behind while returning behind the border.

Timeline

Here’s a concise timeline listing the important events related to the Ardennes Counteroffensive.

June 6, 1944: Allied soldiers land in Normandy

August 25, 1944: Paris is Liberated

September 10, 1944: Allied infantry first enters German territory

5.30 am, December 16, 1944: The Battle of the Bulge is initiated by the German Sixth Panzer Army

December 17, 1944: The Malmedy Massacre carried out by the 1st SS Division

December 18, 1944: Kampfgruppe Peiper captures Stavelot

December 19, 1944: Kampfgruppe Peiper captures Stoumont

December 21, 1944: Bastogne is besieged

December 23, 1944: Peiper returns to German territory; the Fifth Panzer Army takes St. Vith

December 24, 1944: von Manteuffel is denied permission to retreat to German territory

December 26, 1944: Siege of Bastogne is broken

New Year’s Day 1945: Operation Northwind and Operation Baseplate are launched by Hitler

January 7, 1945: Hitler issues retreat order

January 23, 1945: Allies recapture St. Vith

January 25, 1945: German forces in the Battle of the Bulge return to their positions before the offensive

Conclusion and Aftermath

Map of Central Europe with the movements of the German (red) and Allied (green) Armies depicted

In the image given above, the pink line represents the front before the German offensive, the red arrows represent the movement of the various German Divisions, and the green arrows represent the movement of the various Allied Divisions. The upper arrows roughly represent the progress of the Sixth Panzer Army, while the other two arrows represent the movement of the Fifth Panzer and the Seventh Armies.

The ambitious Ardennes counteroffensive ended with heavy losses on both sides, though it had more impact on the Germans than the Allies, and the German army being pushed back to the Siegfried Line.

The Ardennes Counteroffensive was always dependent on captured fuel. Since the Americans emptied or even blew up the fuel reserves in their posts as they abandoned them, the strongest section of the German Army, their armored Divisions, had to be abandoned. This took the thrust out of the German attack by January.

Also, as noted by Field Marshal Rundstedt and General von Mellenthin, the campaign was too reliant on the weather favoring the Germans and keeping the American Air Force out of action. Once the heavy fog in the Ardennes cleared on December 22, American airplanes started to supply food and ammo to defense posts, and Airborne Divisions started to enter the battlefield. One of these, the 82nd Airborne, was instrumental in stopping the Sixth Panzer Army in the north.

Planning an armored charge with no aerial backup against an enemy with clear aerial superiority was a very costly mistake by Hitler that could have been avoided if he had heeded the advice of his own Generals. However, by 1944, the Fuehrer had become so paranoid that it had become impossible to sway him to any opposing view. This was also obvious in his decision to decline permission to von Manteuffel’s army to retreat to Germany when the latter had requested it. If the Fifth Panzer Army had been allowed to retreat before the New Year, much of their heavy armor could have been preserved.

While ordering a massive Luftwaffe strike could have turned out to be a masterstroke, the German chain of command failed in two areas: the first was in gaining information about the anti-aircraft defenses at Allied airbases, and the more inexcusable one was not alerting their own airbases on the route that an invasion of such scale was being planned. When these German airbases saw the large number of aircraft approaching them, they followed protocol and opened fire on them, not knowing the situation. Many German planes were thus felled by friendly fire.

The accounts of Allied casualties in the Battle of the Bulge vary, but most official sources agree on a figure around 80,000-90,000. 19,000 Americans and 200 British soldiers were killed in the battle. This battle took the life of more Americans than any other battle in the Second World War. More than a thousand British soldiers were injured or went missing. Churchill lavished high praise on the American Army for their performance in this battle, in which the Americans had, for the most part, been unassisted by the British Army.

More than 100,000 of the Wehrmacht were killed, captured, or injured. Germany also suffered heavy damages in the form of the almost 800 armored vehicles they had to leave behind due to a lack of fuel, and the 277 planes lost during Operation Baseplate. These losses eliminated a major part of the reserves of the German Army. As a result, the remaining forces were pushed back to the Siegfried Line.

Following the ‘erasing of the Bulge’, the Allies went on an offensive in February 1945. Churchill requested Stalin to do the same from the eastern side, and the Red Army responded with the Vistula-Oder Offensive.

This battle was also notable for being the first instance of white and black Americans fighting alongside each other, with racial segregation abolished. This step was radical at the time, when black soldiers were either employed in service divisions or segregated all-black divisions.